Quick summary: Whether you call them deli meats or lunch meats, as long as they’re properly handled, these sandwich classics are safe for healthy people. Still, it’s best to follow shelf life guidelines to avoid both spoilage and pathogens. After years of being associated with Listeria monocytogenes, a type of infectious bacteria with an uncommon ability to grow in the fridge, lunch meats now often contain antimicrobial ingredients. Even with that extra protection, you’ll have the best and most food safe experience if you don’t stray far from their recommended shelf life. According to the USDA that’s within three to five days of purchase for meat bought at the deli counter and after opening pre-packaged deli meat. All that said, for a healthy person, the odds of getting sick from lunch meat, even lunch meat slightly outside its date label window, are low. And always make sure to keep your food safer—and longer lasting—by making sure your fridge is set to 40 degrees Fahrenheit or below.

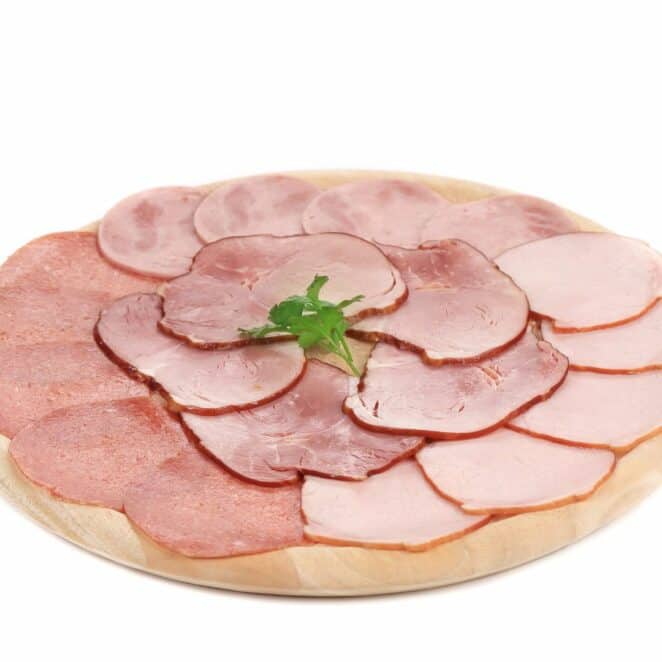

Can you eat deli meats like roast beef, ham, or bologna after their “use by” or “sell by” dates?

We don’t advise eating lunch meats after their “use by” dates. “Sell by” dates are designed to help stores turn over inventory and aren’t consumer safety dates.

My lunch meat only has a “sell by” date. How long is it safe to use?

The USDA recommends using meats sliced at the deli counter within three to five days of purchase, regardless of the “sell by” date. Pre-packaged lunch meats, according to the agency, are good for two weeks, but should be consumed within three to five days after you open them.

But what if, you might wonder, it’s been six or seven days since you bought your sliced turkey and it still looks fine. Do you really need to throw it away?

Kathy Glass, associate director of the Food Research Institute at the University of Wisconsin, put it this way: “Realistically, for a healthy consumer who keeps foods stored at 40 F or less, eating deli meat a couple days past the “use by” probably won’t send them to the hospital….But I prefer not to push my luck since I don’t know the temperature history of the product before I put it into my own fridge.”

Why does the temperature history of the meat matter? We’ve got more details below.

Can you get sick from eating old lunch meat that still looks fine?

You theoretically risk getting sick from Listeria monocytogenes, a bacteria that, with enough time, can grow to infectious levels in the fridge without obviously affecting the taste of the food. Listeria can also grow faster in fridges that are too warm. However, while listeria infections can be quite serious, they tend to strike those who are immunocompromised and/or those who consume very large amounts of the bacteria. Listeria bacteria are relatively common, but cases of listeriosis are rare, and foods are processed and packaged to further reduce the risk.

Lunch meats are handled at the deli counter; any handling makes microbial contamination more likely. They’re also stored for a stretch in the fridge, affording any bacteria more time to grow. Since the meats are usually served cold, the bacteria doesn’t have to contend with heat that could destroy it (a piping hot soup is unlikely to ever give someone listeriosis). But these days, deli meats typically have antimicrobial ingredients to keep listeria at bay, at least while the meat is still fresh from the store.

“The industry has learned a lot because they have been in the press for the wrong reasons. So they’ve adapted,” said Doug Marshall, chief scientific officer at Eurofins Microbiology Laboratories, which conducts studies to help companies set shelf life guidance. “So the vast majority of products on the marketplace will have antimicrobials that prevent growth of listeria over the expected shelf life of the product.”

The antimicrobial ingredients also slow spoilage bacteria growth. This type of bacteria won’t make you sick, but will eventually rot the meat. While each slice of meat will have a different bacterial profile, spoilage microbes are often heartier and may render the meat unappetizing before a problematic amount of listeria could grow. And both spoilage bacteria and pathogens like listeria are less likely to be present if the meat is properly handled. In any event, the meat can get riskier and/or less appealing as you move beyond the shelf life the manufacturer envisioned, and hopefully safety-tested, for the product.

“Part of the way the antimicrobials work is to slow the growth of microbes (and not necessarily stop them forever),” Glass wrote in an email. And if your fridge isn’t set to the best, food safe temperature of 40 degrees or less, listeria could grow faster, especially as time goes by. “So, while the antimicrobial is still functional, it does not make it bulletproof.”

If you’re worried, heating to 165 Fahrenheit kills listeria bacteria

If you ever want a little extra reassurance you can cook your deli meat. The CDC recommends food reach 165 degrees Fahrenheit to kill listeria.

What if lunch meat gets slimy or smells off?

With enough time, spoilage bacteria will probably grow on your bologna, turkey breast, roast beef or other sliced sandwich meat. You’ll know they’re there if the meat feels slimy and/or has a troubling odor. It won’t taste good, even if you heat it to a food-safe temperature. So, pitch that meat and make a mental note to use up the next batch faster.

Why do some deli meats say “use by” while others only list a “sell by” date?

In my local grocery store, it seems that ready-to-eat foods that have been packaged off-site list “use or freeze by” dates, while those that have been prepared at the store, like bundles of sliced lunch meat or sandwiches, list “sell by” dates. When a manufacturer lists “use by” my hope is they’ve researched the product and done some analysis (as we describe here) to arrive at the date, which should include a margin for safety.

When a manufacturer writes “sell by,” that’s not guidance for the consumer, but rather reflects instructions for the store’s staff to ensure proper turnover before the meat goes south. FDA guidelines don’t prescribe consumer-facing date labels for most foods, including deli meats, but they do require vulnerable food packaged on premises to be sold or discarded within seven days. This time frame accounts for the product spending some time in the consumer’s fridge after the seven days are up, according to the agency.

As we mentioned above, the USDA recommends storing freshly sliced deli meats in the fridge and eating them within three to five days of purchase–regardless of the sell-by date. You can also freeze them, which pauses pathogen and spoilage bacteria growth.

Have lunch meats been linked to listeria outbreaks recently?

Yes, but there haven’t been very many cases. In the past several years, the Centers for Disease Control has attributed a handful of listeria outbreaks to deli meats (this one affected 16 people, here’s another that sickened 12 people). Usually, when a case is part of an outbreak it’s because of significant contamination during production or distribution. Isolated cases where someone simply ate meat that was so old it had high levels of listeria are less likely to be flagged as outbreaks because only one person or household would be affected. The CDC estimates that about 1,600 people get listeriosis every year, but determining the cause of each individual case is difficult because symptoms can take weeks to appear.

Products are frequently recalled after listeria is detected on them, but fortunately the bacteria are often detected and the products whisked off shelves without leading to any documented infections. Recalls for foods contaminated with L. monocytogenes are more typically precautions, not reactions to confirmed cases.

What antimicrobials help prevent bacterial growth in deli meats?

Marshall said manufacturers often use salts of certain organic acids to prevent listeria growth in deli meats.

“So you’ll see lactates and acetates as the two predominant ingredients,” he said.

Acetates, he explained, come from acetic acid, which you find in vinegar. Lactates, he said, are naturally found at lower levels in meat, though manufacturers add more lactates to better guard against microbial growth. One source of lactates is lactic acid bacteria, which are also central to making fermented foods like yogurt and pickles. Marshall said you might also see “nisin” and “pediocin” listed as ingredients. Those are compounds that are also produced by lactic acid bacteria; they ward off other types of bacteria. (The ability of lactic acid bacteria to keep other types of bacteria away is why it works so well for us in food fermentation.)

What’s the best way to handle lunch meat?

Use it relatively soon or freeze it after you buy it. Be mindful of the “use by” date, if it has one. Keep your food preparation surfaces and hands clean to prevent contamination. Consider your own health and risk tolerance if you want to push the limit. And make sure your fridge is set to 40 degrees Fahrenheit or below – that temperature makes it harder for problematic bacteria to grow.

SOURCE:

- Douglas L. Marshall. Chief Scientific Officer. Eurofins Microbiology Laboratories. Also: Technical Director, Refrigerated Foods Association.

- Kathleen Glass. Associate Director. Food Research Institute at the University of Wisconsin.

- How long does lunch meat stay fresh?. United States Department of Agriculture Knowledge Article. May 23, 2023.

- Listeria and the special shelf life considerations of ready-to-eat foods. EatOrToss. Dec. 13, 2023.

- Prevent Listeria. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Last Reviewed: November 28, 2023

- Office of Media Affairs. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Email correspondence. Fall 2023.

- Jesus “Jesse” Garcia. Public Affairs Specialist. Food Safety Education Staff. Office of Public Affairs and Consumer Education. USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service

- Shin JM, Gwak JW, Kamarajan P, Fenno JC, Rickard AH, Kapila YL. Biomedical applications of nisin. J Appl Microbiol. 2016 Jun;120(6):1449-65. doi: 10.1111/jam.13033. Epub 2016 Feb 12. PMID: 26678028; PMCID: PMC4866897.

- Khorshidian N, Khanniri E, Mohammadi M, Mortazavian AM, Yousefi M. Antibacterial Activity of Pediocin and Pediocin-Producing Bacteria Against Listeria monocytogenes in Meat Products. Front Microbiol. 2021 Sep 17;12:709959. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.709959. PMID: 34603234; PMCID: PMC8486284.