What exactly happens when food companies set out to determine the shelf life of a new product? In some cases, they enlist the help of outside experts at private or university labs. Today we’re checking in with Microbac Laboratories, an analytical testing company with locations across the United States that helps a wide variety of food producers understand how long their products last. I spoke with Trevor Craig, the company’s corporate director of technical training and consulting, about what exactly that process looks like. Thanks, Trevor, for giving us an insider’s peek at your work!

What kinds of products do you test for shelf life?

We’ll do a shelf life on everything from raw ingredients to finished products. It’s a pretty wide range. We do ready-to-eat meals, fruit chews, some salad dressings, some sauces. I don’t do a lot of foods that are going through a pasteurization process or a ketchup that’s good in the refrigerator for two years. Those don’t come up as frequently as someone who’s using a small facility to make something that’s good for 90 days.

Can you walk me through your process?

So the samples will be shipped to us by the clients. They have to come in the packaging that it’s going to be sold in. That could be sealed with a metal film, put in a vacuum bag or put into a bag with modified air.

From there we immediately test the samples for whatever analysis we’ve agreed on. And then we store at whatever temperature it typically gets stored at. So sometimes we do a storage study at room temperature or we’ll do refrigerated or even frozen studies. And we hold them in that temperature and only pull them out to test. So if you have a 90-day product we pull it six or seven times and test for each individual time point.

Once that’s all done, I’ll evaluate all the data and get back to the client and say, okay, based off the data, we think it’s good for this many days, or could be extended, or isn’t as good as you thought it was.

Do you literally put items on a shelf?

Very simply, yes. In real time studies we place the items on shelves in controlled incubators that mimic the conditions that we are trying to test. So, if it’s refrigerated, we place them in a refrigerator and hold them for the time of the shelf life and test new packages periodically throughout. Now these typically aren’t a refrigerator you would have at home but larger lab or manufacturer versions. For accelerated studies, we do the same thing but at slightly higher temperatures to expedite the process.

What do you test for?

So we could do anything but we’re typically looking at indicator organisms. Lactic acid bacteria is very commonly run. We also run a lot of anaerobic bacteria.

Occasionally we do some chemical testing as well, so things like pH, water activity and rancidity.

Why don’t you test for pathogens like salmonella?

There’s going to be salmonella on raw chicken; that cannot be helped. But if you’re making a finished, ready-to-eat meal, for example, there shouldn’t be salmonella on day zero, which means there shouldn’t be salmonella on day 180, because bacteria doesn’t come from nowhere; it has to get introduced somewhere. So if it’s not there on day zero, it’s not just magically appearing.

Does your testing involve any kind of tasting?

We do not taste in house. Because we work with pathogens in our facilities, that’s a high risk. Also, the client is probably the best at judging their product because taste, smell, and visuals are pretty subjective and changes between products even if they are similar. We recommend clients hold their own samples and do taste, smell, and visual inspections, also called organoleptics, to meet their standards and leave the harder micro and chemical analysis to us.

How often do you pull food to test it?

We typically try to stick to around six or seven times per shelf life. So if they say it’s good for a year, we’ll spread those six or seven over the course of the year. If they say it’s 30 days, we’ll try to do six or seven over the course of those 30 days. We’re pulling to get as many time points as possible to say, “Okay, here’s where we start to see some changes and you know, where things may have started to go awry or hey, it’s never really changed, we don’t have to worry about it.” We’re pulling a separate one each time we’re doing it.

Across all the products in the grocery store, what determines shelf life most often?

I would say a lot of the time it is probably based on organoleptics rather than bacteria. A lot of the shelf lives that you think of as really, really long, involve processes that just don’t have a lot of bacteria. So you’re looking at things like the taste, the smell, the texture as they age.

Products with a much shorter shelf life, like deli items? Those are probably more based off of bacterial load.

And you tend to do more of those deli-style and refrigerated ready-to-eat items?

Yeah, we do a lot more of those, because I think those are the more critical things that people are looking for.

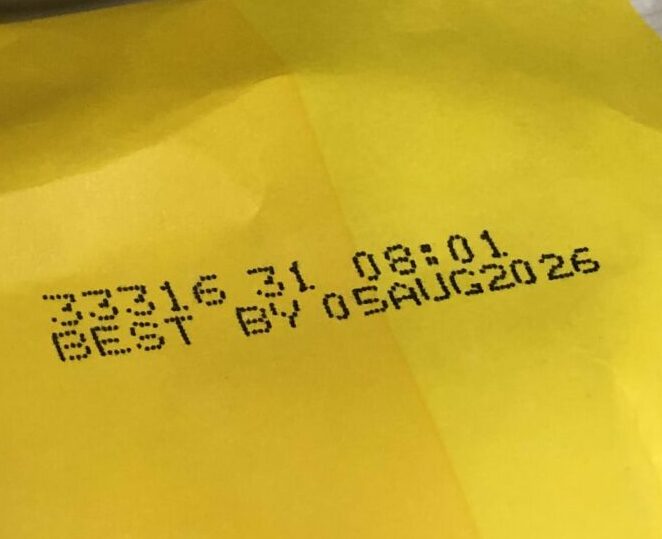

What wording do your clients use after their products go through your process? Best by? Use by?

I just provide the data and the clients make the labels how they want.

Is there anything that you wish consumers understood better about your process or date labels in general?

One of the things that bugs me is how often foods are tossed and how much food waste there is because people have a misunderstanding of food shelf life. I think that’s a shame. Also, I think that there’s a big misconception that shelf life is the end of a food product. Well maybe it’s not the best, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s not still okay to eat.

This conversation was conducted over the phone and by email. It has been edited for clarity and length.