Quick summary: How much you should respect those “use within” guidelines depends on the food’s characteristics (especially how much water is potentially available to microbes and how acidic the food is), how you’ve handled the food, and your own tolerance for pushing limits.

When a food’s packing says “use within X days of opening,” Kathy Glass, associate director of the Food Research Institute at the University of Wisconsin, said that’s usually a signal that the manufacturer is confident it was processed and sealed in highly controlled conditions, but that the product can support microbial growth and will likely decline much faster with exposure to the outside world.

When you break the seal, the food could be contaminated by anything from an airborne spore to a spoon you licked and then stuck back in the jar. Additionally, exposure to oxygen speeds some foods’ decline as it promotes the growth of some microbes and oxidizes fats, making them rancid. Foods packaged with minimal or no oxygen can last a while, but then age quickly once oxygen rushes in after the container is opened.

Keeping a clean kitchen, however, will likely extend the life of the food.

Glass explained: “As long as the consumer is careful about keeping non-ready-to-eat raw food and perishable ready-to-eat foods separate (different cutting boards, utensils, etc.), hands and surfaces are thoroughly washed, they are far less likely to recontaminate the opened package.”

Some, but not all, companies do studies to determine shelf life after opening

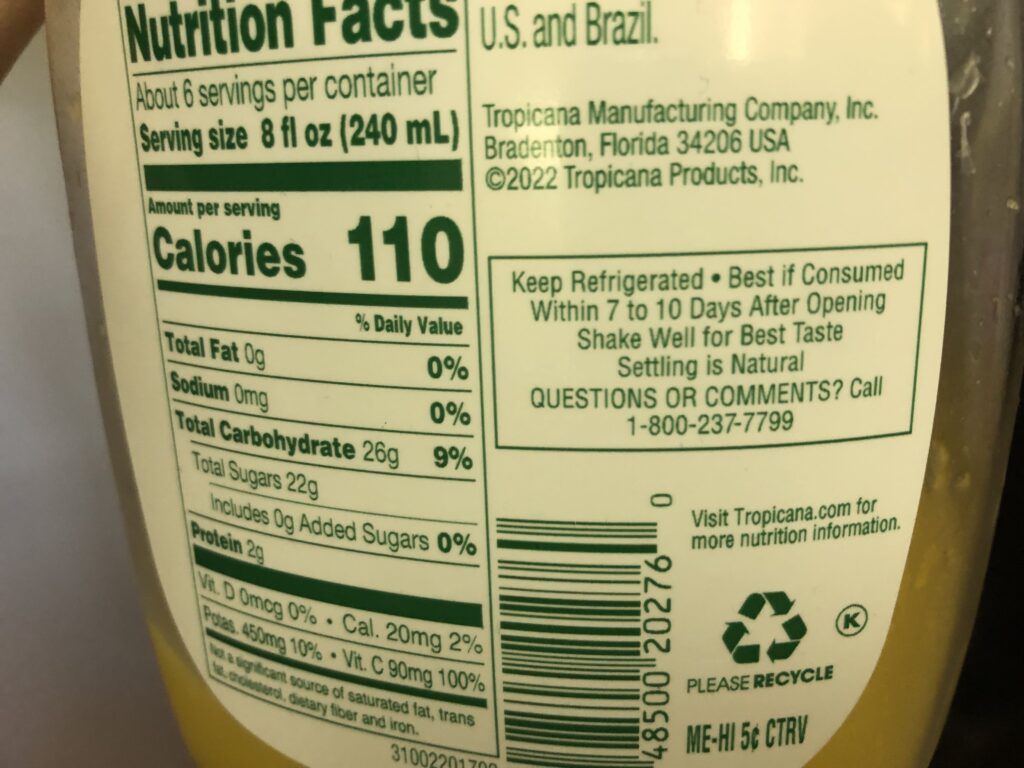

Doug Marshall, chief scientific officer at Eurofins Microbiology Laboratories, which conducts studies to help companies set “use within” guidance, said there are no industry standards for these durations. (For instance, in my own fridge at the moment a bag of shredded cheese says “Use within 5-7 days of opening seal,” and a jug of orange juice says “best if consumed within 7 to 10 days after opening.”)

“It’s make it up as you go along and if you can get scientific evidence to support your duration, that’s great,” he said.

Given the wide range of microbes, storage temperatures and anything else a food could be exposed to, Marshall said that when companies do conduct research, it’s cost-prohibitive to examine everything that could impact a product’s lifespan after it’s opened.

“We pick a small handful of microbes that we know have potential to spoil the product and we see how long it takes for the product to deteriorate…And so we always say, ‘OK, this is what your product could do. We recommend you not set your duration at that point; set it more conservatively. So you have a window of opportunity where the product can still perform even if it’s abused by a consumer.’”

“Abuse” by the consumer could include leaving the opened food at room temperature for long periods of time, storing the food in a fridge that’s too warm, using dirty utensils in the container or otherwise letting the food contact anything that might be sporting some hungry microbes.

How to assess whether your food will be fine beyond the recommended duration

First, consider the temperature of your fridge. If it’s set to the recommended 40 degrees or less, a temperature that slows microbial growth, your food is more likely to last longer.

If a food is acidic (like juice or yogurt) or has little moisture (like aged cheeses), it’s less hospitable to microorganisms and I’m personally quite comfortable using it beyond that recommended window. (According to the European Food Safety Authority juice with a pH of 3.6 or less can’t support the growth of pathogenic microorganisms; juice’s acidity can vary, as you can see in this USDA table.) You can look at a product’s ingredient list for clues about acid content and whether it has any preservatives that would prevent microbial growth. For example, Glass noted that some packaged hummus might have extra acid (indicated by “citric acid” or “lemon juice” listed in the ingredients) to help preserve it; and some might not.

I also visually inspect and sniff test anything if I feel I’m pushing the limit.

But I’m more careful with foods that aren’t dry and/or highly acidic and tend to treat them like any other leftovers. The USDA recommends consuming leftovers within three to four days. That’s how I’d handle a can of corn once opened, for example. The canning process renders the corn “commercially sterile,” making it perfectly safe at room temperature while everything is still sealed. But once the can is opened, the corn needs to be stored in the refrigerator and eaten relatively quickly. If you wait too long, spoilage microbes that can grow at refrigeration temperatures will most likely settle in, but it’s also not impossible that a pathogen could grow too.

As with any food, good kitchen practices can help your food last longer

And just to reiterate the importance of keeping a clean kitchen: while microbes are present in even the most hygienic conditions, if you follow good food management practices (like not using a utensil that’s touched raw meat on any food that’s left uncooked) you’re less likely to contaminate those open containers in the first place. And, apologies for sounding like a broken freshness seal, but keep your fridge set to 40 degrees or less and your food will last longer.

SOURCES:

- Kathy Glass. Associate Director. Food Research Institute at the University of Wisconsin.

- Douglas L. Marshall. Chief Scientific Officer. Eurofins Microbiology Laboratories. Also: Technical Director, Refrigerated Foods Association.

- Guidance on date marking and related food information:part 2 (food information). EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ),Konstantinos Koutsoumanis, Ana Allende, Avelino Alvarez-Ordo~nez, Declan Bolton,Sara Bover-Cid, Marianne Chemaly, Robert Davies, Alessandra De Cesare, Lieve Herman,Friederike Hilbert, Maarten Nauta, Luisa Peixe, Giuseppe Ru, Marion Simmons,Panagiotis Skandamis, Elisabetta Suffredini, Liesbeth Jacxsens, Taran Skjerdal,Maria Teresa Da Silva Felıcio, Michaela Hempen, Winy Messens and Roland Lindqvist. EFSA Journal. European Food Safety Authority. Adopted March 10, 2021.

- Labeling Guidance: Best practice on food date labelling and storage advice. WRAP, Food Standards Agency (UK), Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (UK).

- pH of Selected Foods. Pathogen Modeling Program. United States Department of Agriculture. Agricultural Research Service.

- Leftovers and Food Safety. Food Safety and Inspection Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture.

- Molds on Foods: Are they dangerous? United States Department of Agriculture. Food Safety and Inspection Service.