Ever wondered about dirt on your produce? Maybe you’re not sure you scrubbed every last bit of grit off your potatoes. Or you’re just generally feeling a little funny about the sandy film on your farmers market cucumbers. Perhaps just as you’re about to take a bite of salad you notice a little speck of dirt clinging to a leaf.

Sure, soil isn’t the seasoning you had in mind, but is it risky? Is it safe to eat the food?

Here’s the deal: To prevent illness you should definitely, always get your produce as clean as you can. But, no, if you occasionally ingest some dirt you probably haven’t doomed yourself to gastrointestinal distress. Why? It’s complicated. Here’s the nitty gritty on dirt on vegetables.

Is dirt dangerous?

Lots of microorganisms live in soil. But soil isn’t, by default, riddled with pathogens that will lead to foodborne illness in people. In fact, some scientists argue that early exposure to dirt and its multitude of largely benign microbes is good for children. Still, soil anywhere can become contaminated with microorganisms that can make you sick (one way: if a pathogen-carrying dog takes a potty break).

So most soil probably won’t cause illness if accidentally ingested, but what happens if soil containing pathogens does land on produce?

The pathogen will likely contaminate the produce. What’s more, while sunlight might kill a pathogen on a smooth, sun-exposed surface of, say, a tomato, the dirt could provide some protection and enable the pathogen to survive. But, there’s still hope. If best practices are followed from farm to market, and if you give your fruit or vegetable a good scrub during your food prep, the risk will be minimized.

Are there any special risks with soil on a farm?

If irrigation water becomes contaminated, it can spread pathogens in the field, either directly onto the crops or onto soil that may later contact the crops. Raw manure applied to the ground as a fertilizer can also contain bacterial baddies like Salmonella and dangerous strains of E. Coli. And sadly, disease can also spread on farms that don’t provide adequate training, bathroom facilities, and an otherwise supportive environment for their workers.

In the U.S., farmers follow laws and guidelines to keep their produce as contamination-free as possible, but, of course, the risk can’t be entirely eliminated.

Once soil is contaminated does it stay contaminated?

Bacteria that can cause food-borne illness on raw produce are most at home in the warm, nutrient-rich confines of the human digestive tract. They have a much harder time surviving in soil, where they face greater competition and harsher environmental conditions and will eventually die.

How often do people get sick from eating produce contaminated by soil?

It’s hard to say, but I struggled to find documented outbreaks where disease spread via soil. The only one I found happened more than a decade ago when soil on leeks and potatoes was thought to be the source of about 250 E. Coli infections in the United Kingdom. Even in that case though, soil was never definitively confirmed as the source of the contamination.

Food-borne illnesses can come from many sources: As of this writing, in October 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lists 12 “selected multi-state outbreak investigations.” Food sources range from cake mix to frozen cooked shrimp and only one outbreak is linked to fresh produce: packaged salads. And that was connected to a company that grows its leafy greens indoors, without soil.

All that said, many isolated cases of food-borne illnesses, especially those that people recover from fairly quickly, aren’t reported and are never linked to the food that caused the problem. If enough people get seriously sick, health officials identify an outbreak. But even then the cause or specific food can’t always be pinpointed.

Is squeaky clean looking produce the safest produce?

While you should get your produce clean, swearing off root vegetables or other produce that touches soil just because they’re more likely to have some hitchhiking dirt would likely have a marginal effect on your food safety risk—and would deny you nutritious food!

All raw fruits and vegetables carry some risk because we don’t subject them to bacteria-killing heat before eating. A food can look squeaky clean but still carry harmful bacteria from touching a contaminated surface or unwashed hands.

United States Department of Agriculture microbiologist Manan Sharma put it this way: “Just because it looks clean doesn’t mean it doesn’t have a certain risk and just because it looks dirty doesn’t mean it’s going to get you sick. It also doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t wash off the soil or the dirt. You definitely want to wash it off.”

What about soil that’s really hard to scrub off?

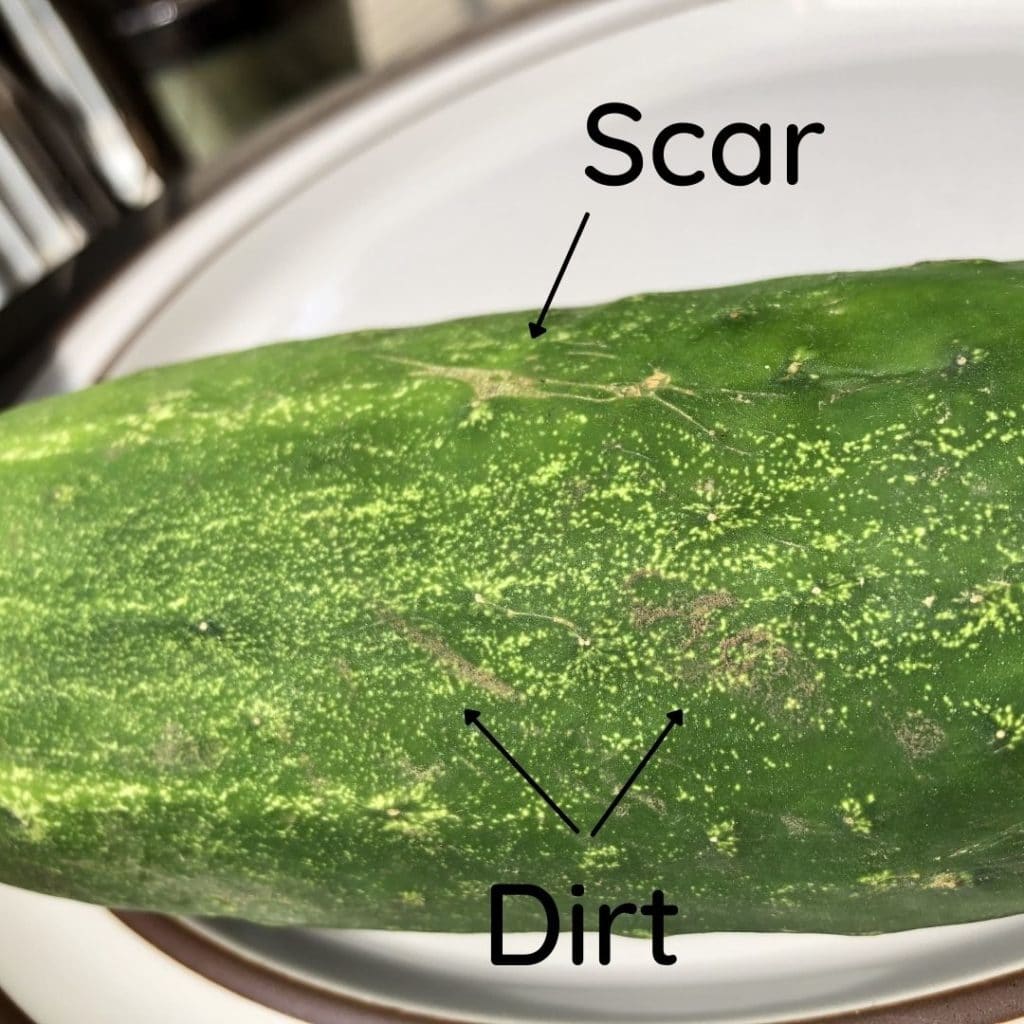

Some soil is just stubborn. But in other cases, it may not actually be soil. The cucumbers pictured below have some dirt, but also some scarring that might look like dirt.

This butternut squash may look like it has caked-on mud, but that’s actually the squash’s attempt to heal an injury.

My favorite farmers market stand uses raw manure on their crops. Should I worry?

Probably not. If farmers follow best practices, researchers believe the risk is minimized.

Manure is a great fertilizer, but since healthy cows and chickens can carry microbes that can sicken people, their manure has to be used carefully. In the U.S., organic farmers, who don’t use chemical fertilizers and often rely more on manure than conventional farmers, are required to wait 90 to 120 days (depending on whether the crop touches the ground) after applying raw manure before harvest. That reflects the current best understanding of how long it takes for problematic bacteria populations to dwindle.

Some farmers use treated manure (which has reached pathogen-killing temperatures), but that can add complexity and expense to farming operations. As part of the Food Safety Modernization Act of 2011, scientists are studying bacterial survival in manure. This will inform new rules for all farmers on the safest ways to handle manure.

Would it be easier to just stop using manure as a fertilizer?

Not so fast. Manure is readily available and great for crops. It fertilizes without synthetic chemicals. Asking farmers to dispose of it via other means and bring in new types of fertilizers could lead to environmental problems and increase costs.

SOURCES CONSULTED:

- Manan Sharma. Research Microbiologist. Environmental Microbial & Food Safety Lab. Agricultural Research Service. United States Department of Agriculture.

- Produce Safety Product Issue Brief. FARM WORKER HEALTH AND HYGIENE Robert B. Gravani, Ph.D., Department of Food Science, Cornell University.

- E. Coli Infection. Healthy Pets, Healthy People. Diseases. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Soil Building – Manures and Composts. Agricultural Marketing Service. United States Department of Agriculture.

- Raw Manure under the FSMA Final Rule on Produce Safety. U.S. Food & Drug Administration.

- How to wash fruit and vegetables. National Health Service (U.K.)

- Food Safety: Soil Amendments. Center for Agriculture, Food, and the Environment. University of Massachusetts Amherst.

- Food Microbiology: An introduction. Karl R. Matthews, Kalmia E. Kniel, Thomas J. Monteville. Fourth Edition. ASM Press. Washington, DC. 2017.