On a blue-sky day in September I went to the woods with an open mind and also, erm, an open mouth.

My objective was to sample and contemplate the food that can be obtained from the plants, shrubs and trees native to my home region, the Mid-Atlantic of the United States. The trees lining the sidewalks I walk every day seemed, to me, vital for cleaning our air and enlivening our spaces, but not for filling our plates. Shrubs and their ominous berries always looked like poison. And the weeds in the grass? Ok, maybe I knew that some people cooked with dandelion greens, but that was it.

As someone determined to research the safety of any questionable-looking food before consuming it (for proof please see the rest of this website), I certainly wasn’t about to sample the forest’s nuts, berries, leaves and roots without a guide. And so, on this crisp morning, I found myself at Piscataway Park in Accokeek, Md., enjoying granola and yogurt topped with jam made with American persimmons harvested literally a stone’s throw away. Our guide for the Wild Edibles Walk, Katherine “KC” Carr, asked everyone to introduce themselves and explain why we wanted to learn about what we can eat in the forest.

People said they came because they loved food, because they loved eating locally and learning about what’s all around them. One woman said it was part of her doomsday prep plan. I could not tell if she was kidding. Another, pointing toward her toddler, who spent breakfast collecting acorns off the ground, told us her son is drawn to wild berries and she wants to “know when we don’t need to call poison control.” As if on cue, KC, regenerative agriculture coordinator for the Accokeek Foundation, passed around a flyer that flagged signs a plant could be poisonous. Just a few examples: milky sap, bitter or soapy flavors, spines, white, green or yellow berries. It’s literally a jungle out there.

And then, we started walking.

Our first stop was a pretty purple flower, growing next to a fence post. “Chicory!” KC said. People chop up the roots, roast them and treat them just like coffee beans. (And, yep, it’s the same chicory found in New Orleans’s famous coffee.)

This tour, one of a series that runs throughout the year, is part of the educational programming offered by the Accokeek Foundation, which focuses on history, culture, agriculture and conservation, especially as it relates to the indigenous landscapes within Piscataway Park. As we walked, we passed the National Colonial Farm, where the foundation showcases 18th century agriculture, and we headed for the area the foundation has named the National Food Forest. This “food forest” isn’t deliberately seeded with food-bearing plants, but rather is managed to keep out invasive plants and allow the forest to show off all the food it naturally produces.

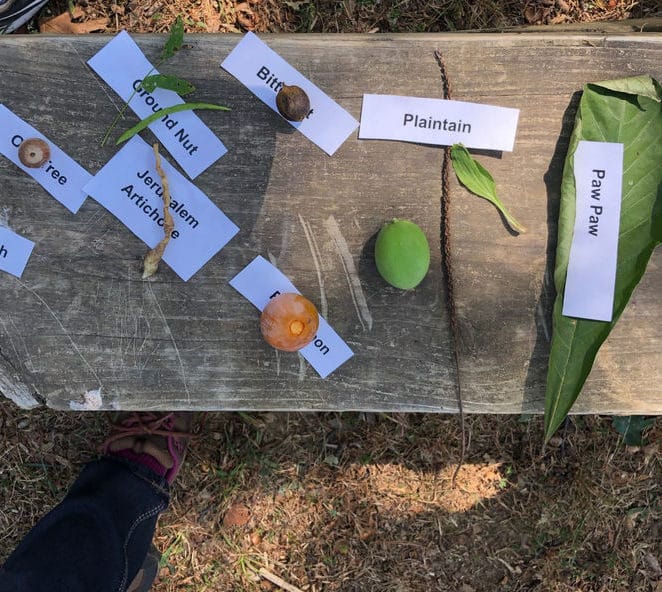

A few minutes later, we were standing in a circle and staring at a little bundle of leaves on the ground. I recognized the tiny, oh-so-familiar plant from athletic fields and lawns, where it nearly blends in with the grass: a few leaves surrounding a bumpy, narrow shoot. This is plantain, we learned. Despite its name, it has nothing to do with bananas or the tropics, but it IS edible. Marge Rich, another foundation staffer, extolled its medicinal virtues. You can eat the leaves, the seeds, everything, she said.

Next up was a sumac tree. Not poison sumac, which has white berries, KC explained, but a perfectly safe type of sumac with edible red berries that grow in bundles. We each reached into the tree’s branches and picked a few peppercorn-sized samples. My berry was mostly seed, but the juicy exterior was tart and spicy, so it made complete sense when KC explained that people crush them and add water and honey for a sumac version of lemonade.

Deeper into the forest we met black walnuts, good in breads and cookies. And another little red berry, this one known as spicebush and said to taste like allspice. I broke a berry open with my nail, held it up to my nose and fell in love. It smelled like licorice and pine, like my local forest’s answer to pumpkin spice.

This food forest represents the Accokeek Foundation’s efforts to revitalize the land, including woods, savanna and meadows, with an eye toward its indigenous past. While most Washingtonians couldn’t recognize a pawpaw, we were now clustered around a small tree that the region’s Native Americans knew well.

Green and vaguely resembling a mango, the pawpaw fruit looks exotic. Its flavor also suggests the tropics, tasting like a mango and banana mashup. It’s delicious, Marge assured us, but the pawpaws on this tree weren’t ripe enough to eat. Ripe pawpaws are dark brown, nearly maroon in color.

Next was cattail, “You can eat cattail?!?” someone exclaimed, as we learned that the marsh plant offers something different each season. In spring, young shoots can be peeled and prepared like asparagus. In the summer immature flower spikes (the areas that will become the brown “tails” the plants are known for), can be boiled, buttered and eaten like corn on the cob. In the fall and winter, the roots can be collected and turned into flour.

We sampled little green beans called groundnuts, and we rose up on our tip toes to pull tiny juicy balls off a vine of something called possum grape. KC talked about acorns, how they can be collected, boiled, roasted and ground into flour. It became increasingly clear that while we can harvest food from the forest, it’s simply a lot of work.

Our final stop was a tall tree with a bark that KC gushed about—look at how the bark makes a square pattern, she said with admiration. Then she picked a small orange fruit up off the ground. It looked kind of like a squishy, gelatinous stone fruit.

A persimmon! The very same from the jam we ate hours ago—had it really been hours? KC described them as delicious and tart, but also challenging to work with. Persimmon trees native to this region are small and filled with seeds.

We returned to a beautiful buffet of forest food (set up by Accokeek staffers while we strolled). I sampled a honey-fermented plantain leaf, but admit I found it quite fibrous. On the other hand, plantain leaves blended imperceptibly into a basil pesto. The plantain showed up again in crackers, this time, their seeds, which added bulk. There were also cookies baked with persimmon, a hot drink brewed with chicory, and then my favorite: a cold tea made by boiling spice bush twigs.

On a wooden bench, I sipped the tea and peered at the forest. I’d never look at a red berry the same, I realized. And while I’m not about to gather acorns to make flour or pull up the plantain growing between the cracks in the sidewalk to make crackers, there’s something lovely and satisfying about knowing that I could.

The next Wild Edibles Walks are scheduled for May 2, 2020 from 9-12pm and Sept 26, 2020; 9-12pm. Tickets aren’t yet on sale, but check Accokeekfoundation.org for updates!