What you see/smell: Your shredded Parmesan (or other Parmesan or aged cheese) might look normal, but have a metallic or chemically taste.

What it is: It oxidized! Possibly some other things went wrong too, but oxidation is most likely.

Eat or toss: Toss. If it doesn’t taste good, it’s not worth eating.

Over time, oxygen can degrade the flavors in a cheese like parmesan

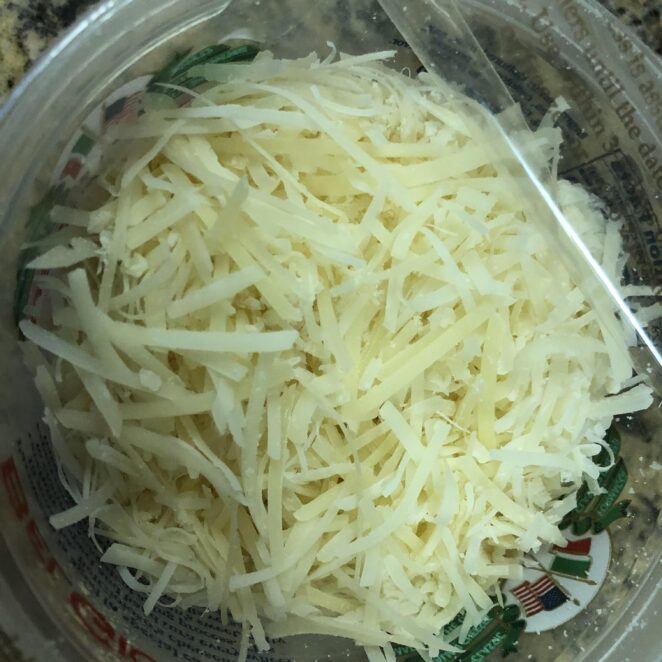

The scene: I’m working on a pasta dinner, reaching into the fridge for that tub of shredded Parmesan cheese I bought a while ago. It looks full and I assume it’s never been opened. But when I pull off the lid I discover that the plastic seal had already been peeled off, presumably because we needed just a tiny bit more cheese during a spaghetti dinner I’ve long forgotten. How long has this parm been open? I have no idea!

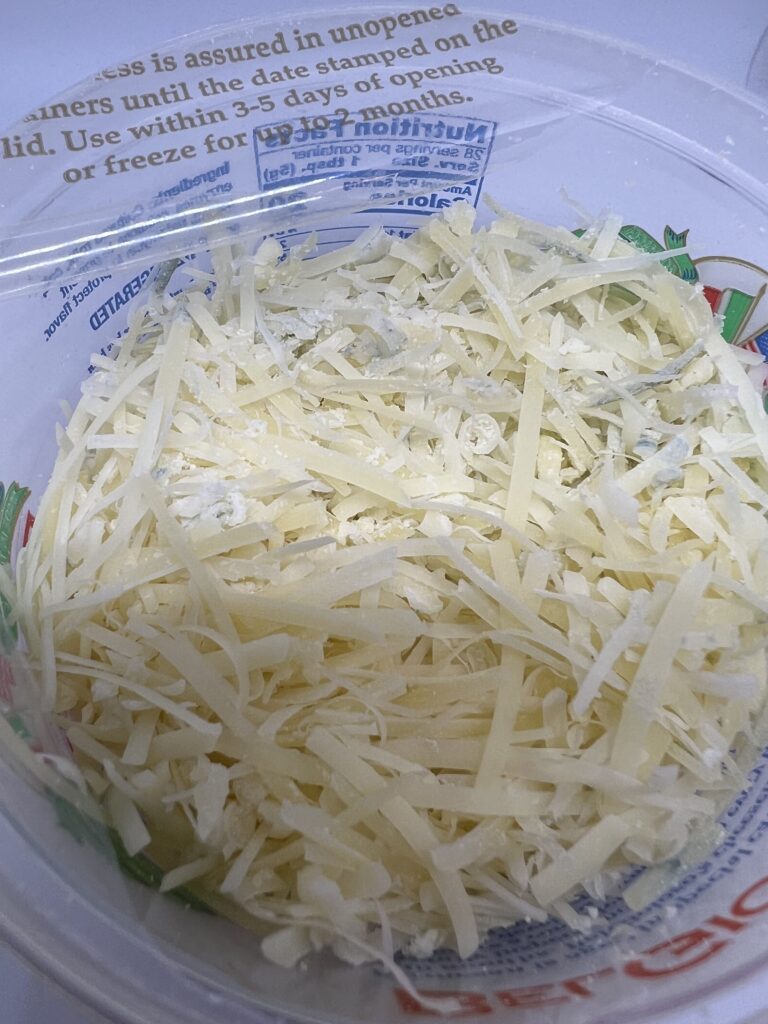

But the Parmesan still looks fine, so I’m not worried. I grab a pinch to eat and this is when I am stopped in my spaghetti-night tracks. It tastes WEIRD! Not spoiled weird, not cheesy weird, but kind of like metal and kind of like random chemicals.

I look in the tub again, wondering if there might be a cluster of something nefarious growing that I had missed. But it looks SO normal. And it smells, well, kind of normal, I think?

I offer some to my favorite test subject, erm spouse. Maybe it’s just me? Cheeses are definitionally funky tasting foods.

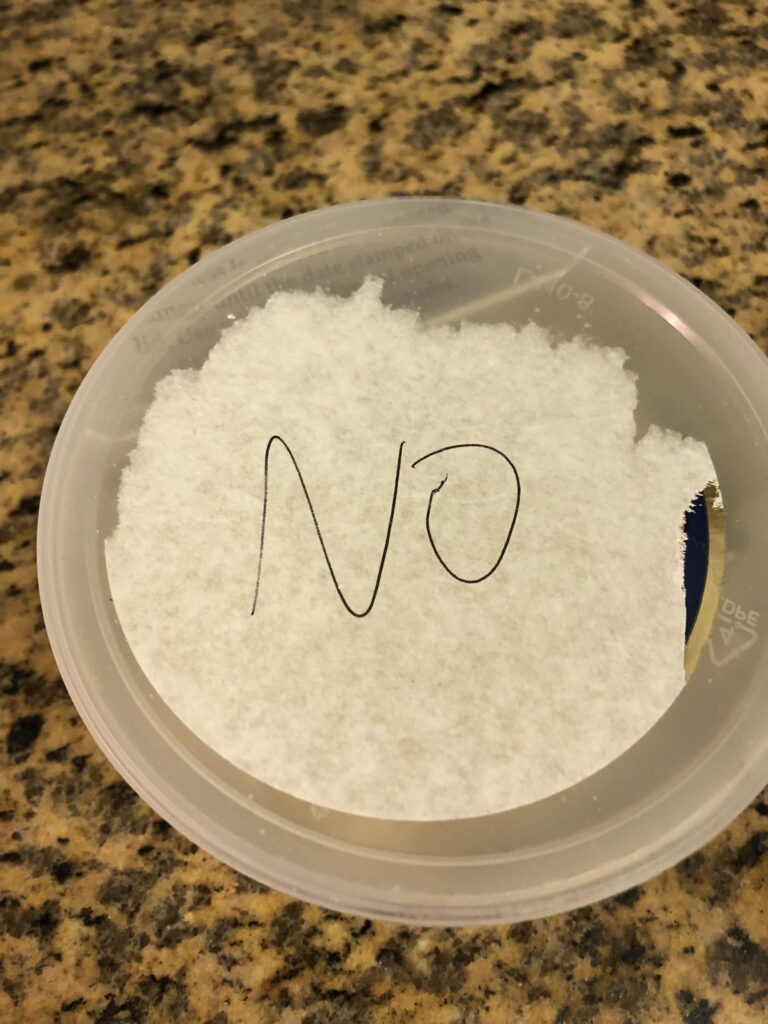

He takes one whiff and wants nothing to do with it. I’m not ready to part with it just yet (SCIENCE!), but he is not ready to ever get near it again, and alters the container just to be sure.

So, what was going on? I asked Nicole Martin, an assistant research professor in dairy foods microbiology at Cornell University. She said the Parmesan probably oxidized, meaning that reactions with oxygen broke some of its fats down into different kinds of icky-smelling molecules. That would explain why the off flavors were more chemically and less spoil-y.

“Some people are really sensitive to that oxidized flavor and it is often described as metallic or chemical, those kind of things,” she said.

Martin also noted that cheeses, especially an aged cheese like Parmesan, often have complex flavors and long histories – so there’s the potential for other things to be going on too.

“It could be a combination of different things, certainly,” she said. “But my first thought was oxidation.”

In any event, it tasted too off for us to eat, and eating rancid food isn’t the best idea, so we’re deeming this a toss.

Why do cheeses last longer while the packages are still sealed?

Products like this tub of Parmesan cheese are typically sealed with a special formulation of air for what those in the food industry call “modified atmosphere packaging.” The “modified atmosphere” is made up of basically the same stuff that dominates regular air–carbon dioxide and nitrogen–but with no oxygen or a very small amount of oxygen. That means less opportunity for oxidation, so the product lasts longer (in produce, lower oxygen levels can also slow respiration, which slows decline). These products are also sealed up in the (hopefully!) clean environment of the factory so they’re free from contaminants. (But factory contamination isn’t impossible: here’s what happened when I opened yogurt that probably was contaminated before the manufacturer sealed it up.)

The carefully calibrated air and contaminant-free cheese is, of course, disrupted once we open the package. Then, anything from my cheese-pinching fingers to a sneeze to spores floating by can lead to new, unwelcome, microbial life settling into this old cheese and possibly growing. And any neighborhood oxygen can get busy oxidizing.

The difference between the controlled environment inside the package and the unknown oxygen-filled microbiological ecosystem once it’s opened is why products may have a “best by” date that’s months in the future, but instructions that, like on this tub of shredded cheese, say, “use within 3-5 days of opening.”

Not that the “use within 3-5 days of opening” guidance is anything to live or die by. It’s often a conservative best guess, if that. I routinely use things long after the “use within” guidance. While it’s a personal choice, I’m comfortable doing this if I know I’ve stored the product properly (usually by refrigerating it), it looks good, and I don’t detect any off odors or flavors. I’m also more likely to give a longer grace period to foods less likely to support microbial growth. Anything acidic, low-moisture (like an aged cheese), or packed with salt or sugar is less inviting to microbes.

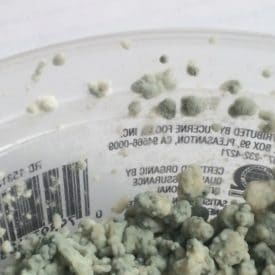

In my past experiences, I’ve seen fungal growth on old Parmesan, but haven’t noticed oxidation before the mold showed up. Martin noted that a cheese’s susceptibility to oxidation varies.

“It depends on a lot of factors that could be all the way upstream to the farm that the milk came from,” she said. Those factors include exposure to oxygen and light and even how much vitamin E was in the cow’s feed.

“Every milk supply has a different propensity for oxidation.”

Post script:

I left the Parmesan in the fridge for at least another month. My test subject, erm, spouse, asked me about it several times. But I wanted to see what happened. And, sure enough, in that time it did grow mold. Probably a penicillium mold, given the greenish blue hue. (As we’ve noted in other posts, there are a number of penicillium molds, some of which give us antibiotics, others blue cheese and still others toxins we don’t want to consume). Martin’s best guess was that the off flavors we encountered before the mold showed up had nothing to do with the future mold colony. In any event, it was off to the compost for this cheese.