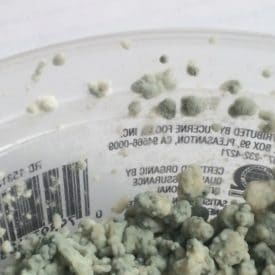

What you see: A green substance on the surface of the yogurt.

What it is: Mold.

Eat or toss: The mold could have penetrated deeper than you could see, making the yogurt taste gross. Toss. But if you’re desperate, or just curious, read on.

Is it safe to eat yogurt with a moldy spot on the surface?

I had just peeled the seal off this tub of yogurt and scooped some out for my toddler when, to my horror, I saw a greenish patch on the yogurt’s surface.

Alert! Mold! Alert! The yogurt is moldy!

Per USDA guidelines, any time a soft food, like yogurt, sports uninvited, visible mold, you shouldn’t eat it. The reasoning is that the mold could have penetrated beyond the areas you see. While many molds are harmless, some produce toxic substances you don’t want to consume.

But the USDA’s advice here is general. Let’s dive a little deeper into this tub of moldy yogurt. Today’s diving partner is Nicole Martin, associate director of the Milk Quality Improvement Program at Cornell University’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

“It’s most likely not a food safety issue,” she said after inspecting my image. “This is just spoilage.”

The green cast to the mold suggested to Martin that it’s a type of penicillium (Yep! From the same genus of molds that brings us the antibiotic penicillin, but no, eating this yogurt won’t cure your bacterial infections.) Penicillium species, Martin said, are the molds that most often spoil dairy products.

The penicillium genus is diverse, with some molds producing helpful antibiotics, others helping us make cheese and still others producing harmful toxins. Penicillium molds that generate significant toxins are typically found in grains, nuts, and certain types of produce. The greatest and most likely threat Martin saw in this tub was that the yogurt would taste bad.

Molds release enzymes that can make food taste icky

Mold releases enzymes that break the food down into components that are more accessible for the fungal organism, and, often, much less appetizing for us human organisms.

“Those enzymes are going to cause some bitter flavors, some unpleasant flavors and odors that are going to diffuse through the product,” she said. “So if I open a cup of yogurt and it’s got mold on it, I’m going to toss that because most likely you’re going to get an unpleasant experience with it.”

Another reason to be careful with moldy food, especially on fruits and vegetables, is that the mold might not have come alone. In produce in particular, if a mold is thriving in a wet, soft spot, some invisible bacteria might be, too. This is less of an issue with something like yogurt though. It’s so acidic that most bacteria (aside from the lactic acid bacteria central to yogurt production) already would struggle to grow in it.

“It’s not that there aren’t some pathogens that can survive under those conditions, but there aren’t many and they don’t usually thrive under those conditions,” Martin said.

“So, typically what we’re seeing with yogurt is much more quality related issues and mostly that’s surrounding different fungi because fungi can grow at much lower pH than most bacteria can.”

Swollen, fizzy yogurt containers: The Chobani case

Dedicated yogurt eaters may remember an episode in 2013 when swollen, fizzy Chobani yogurt cups landed on grocers’ shelves. Consumers reported that the product looked like “yogurt soup” and tasted “really old,” like “wine.” Remember those flavor-altering enzymes we talked about above? Sounds like they were in full force here. This fungus was probably also releasing some carbon dioxide, which resulted in the fizziness and bloating.

Chobani recalled the yogurt, did a thorough scrub of its manufacturing plant in Twin Falls, Idaho, and reported that an issue with a pipe allowed contamination by a fungus called mucor circinelloides. (This species is a wholly different character than the mold leaving a green half moon on the yogurt pictured above. Mucor circinelloides can easily grow as a yeast or a fungus, and switches between those forms based on environmental conditions, Martin told me. Growing in yeast form produced a gas and changed the yogurt’s character, but didn’t leave behind any signature moldy fuzz.)

Here’s where things get extra interesting: While Chobani and an independent scientist said the fungus in question was primarily a spoilage microbe and wasn’t usually harmful to people, more than 200 people reported becoming ill with nausea, vomiting and diarrhea after eating the yogurt.

But no one was ever able to link those reports of illness to the fungus itself. As an FDA spokesperson told Food Navigator, making a connection is tough given the many variables, including individual health and what else a person may have consumed.

Researchers at Duke University got some of the contaminated yogurt from a Texas couple, isolated the fungus and reported that it caused illness in mice. But, Chobani and Randy Worobo, a Cornell food scientist, questioned their analysis, pointing out that there was a vast difference between injecting a fungus into a mouse’s bloodstream and a person eating yogurt containing the same fungus.

What are you, dear yogurt eater, to do with all of this? It’s simple: don’t eat fizzy yogurt from swollen cups! (And definitely do not inject it into your bloodstream.)

Be a good yogurt citizen! Tell the manufacturer!

In the Chobani case, as with the yogurt I almost fed my toddler, the product was suffering before the end user had even broken the seal.

Such circumstances suggest contamination during manufacturing, Martin said. When you see mold on yogurt in a new, freshly opened container it’s also possible it spent time at warmer temperatures, which cause microbes to grow faster.

If you ever encounter mold in a freshly opened tub like these, contact the manufacturer. They’ll probably make it up to you with a reimbursement and/or coupons for free products. You’ll also do them a favor by alerting them to a potential systemic problem. You could actually help prevent future food waste.

If, on the other hand, you discover mold in your yogurt after it’s sat open in your fridge for who knows how long, then that mold probably came from your home. That’s exactly what happened in the image below. (Based on the blue/green color and the fact that it’s growing on a dairy product, this is also likely a penicillium species.) While we can’t see them, mold spores often lurk in the air and on surfaces in our kitchens and fridges.

Also worth keeping in mind: Your yogurt won’t go bad and sprout mold the second it hits its printed date. That’s just the manufacturer’s guess as to when the food will pass its peak quality.

In yogurt that’s been properly processed and kept chilly during transit and at the store, mold growth will depend on factors like your kitchen environment and how often the product has been in and out of the fridge. But, the “expiration date” can still give you a clue to the age of the yogurt; an older product is more likely to go moldy. On the other hand, if the yogurt still looks good and smells good, even if it’s past date, it’s still probably fine to eat.

SOURCES:

- Nicole Martin. Associate Director, Milk Quality Improvement Program. Cornell University. College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

- Molds on Foods: Are They Dangerous? United States Department of Agriculture. Food Safety and Inspection Service.

- Mycotoxins. World Health Organization. May 2018.

- FDA satisfied with protocols in Chobani plant post moldy yogurt incident. Elaine Watson. Food Navigator. July 9, 2014.

- Chobani blasts “irresponsible” study on moldy yogurt; Authors stand by their paper. Elaine Watson. Food Navigator. July 7, 2014.

- Recalled Yogurt Contained Highly Pathogenic Mold. Marla Vacek Broadfoot. Duke Today. July 8, 2014.

- Chobani pulls “unnervingly fizzy” yogurt from shelves. Roger Ridell. Food Dive. Sept. 4, 2013.